Question:

An experienced birder friend told me that I should not give peanuts to birds because the birds do not have salivary glands and thus, they can choke and die after eating those brown skins coating the kernels. Is this true?

Response:

This is a new one on me. I do occasionally get questions from folks wondering whether birds can choke on sticky peanut butter and my answer is always the same…..

There is no evidence to my knowledge to support such a claim. Now, your question is a wee bit different because you have been told by a birder whom you trust that Blue jays, eating peanuts in the shell, which they adore by the way, can choke on that rather dry brown skin coating the peanut kernel because they have no salivary glands. In my forty years of researching and responding to questions about feeding birds, I have never heard of a case of a Blue jay or any other bird species for that matter having difficulty swallowing those brown peanut skins. And I know for a fact that birds do have salivary glands, but just not an overabundance of them compared to mammals. It also varies among different kinds of birds depending on their diet. For example, those birds that eat a lot of dry grains and seeds have more productive, more complex salivary glands than birds that eat small animals and fish. The saliva is used in the early part of digestion to break down carbohydrates and moisten the food. If I still have not convinced you, or your reputable birder friend, consider the fact that Blue jays in particular are well known to consume loose mortar and paint flakes, presumably for the mineral benefits. Now, if that would not make a bird choke, I do not know what would.

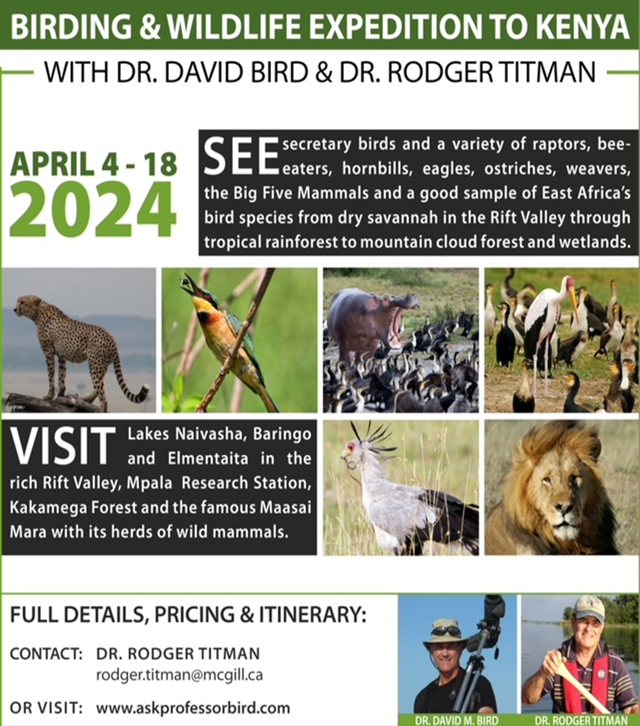

David M. Bird, Ph.D., Emeritus Professor of Wildlife Biology, McGill University www.askprofessorbird.com

David M. Bird is Emeritus Professor of Wildlife Biology and the former Director of the Avian Science and Conservation Centre at McGill University. As a past-president of the Society of Canadian Ornithologists, a former board member with Birds Canada, a Fellow of both the American Ornithological Society and the International Ornithological Union, he has received several awards for his conservation and public education efforts. Dr. Bird is a regular columnist on birds for Bird Watcher’s Digest and Canadian Wildlife magazines and is the author of several books and over 200 peer-reviewed scientific publications. He is the consultant editor for multiple editions of DK Canada’s Birds of Canada, Birds of Eastern Canada, Birds of Western Canada, and Pocket Birds of Canada. To know more about him, visit www.askprofessorbird.com or email david.bird@mcgill.ca.

CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENT | News, Alexandra Mae Jones CTVNews.ca writer

This bird isn’t just half green and half blue — it’s half female and half male

When the bird first appeared in front of bird watchers in Colombia, it was clear from its unique plumage—bright green on the left half of its body and blue on the right half, split neatly down the middle as though two birds had been glued together—that it was something special.

But what amateur ornithologist John Murillo didn’t know as he snapped a photo of this rare, half-female, half-male bird, was that this was the first time in more than 100 years that this phenomenon had been recorded among this species of bird.

It’s a rare condition called bilateral gynandromorphy, in which one side of an organism shows male characteristics and the other shows female.

This is only the second time that a bilateral gynandromorphy has ever been observed in a Green honeycreeper, a small bird that is commonly seen across a swathe of territory stretching from southern Mexico to southeaster Brazil.

It is also the first time that a living Green honeycreeper with bilateral gynandromorphy has been found.

The phenomenon arises from an error during female cell division to product an egg, followed by double-fertilization by two sperm.

Cases of this unique condition have been recorded across numerous animal groups, but its most easily spotted among animals with strong sexual dimorphism distinguishing males from females, such as birds.