Question:

A few weeks ago, a friend and I observed an amazing spectacle. It involved a flock of thousands of European starlings wheeling about in an undulating dark mass. What keeps them from colliding into one another and how do they determine to turn in the same direction at the same time?

Response:

I have seen these huge wheeling masses of starlings ranging from 500 to 100,000 birds on a number of occasions myself and they are beyond a doubt one of the most spectacular ornithological events one can witness. Among other names. They are generally referred to as murmurations. Apparently, the starlings are moving at speeds in excess of 90 miles an hour, which begs the question—what keeps them from colliding—and your specific question—which bird decides the given direction of the flock.

Years ago, I met a wildlife photographer who specialized in taking photos of these eye-catching ornithological spectacles. And upon examining the photos quite closely, one could invariably see a raptor like a falcon or hawk constantly worrying the flock trying to pick off one of the outside birds. That is what drives the starlings to bunch together and then spread apart. No bird wants to be on the outside! The current thought to date on how the starlings maneuver through the air in such a mass is as follows. It is a nearest-neighbor phenomenon—each starling only communicates with about a half-dozen or so birds closest to itself. They basically follow their cues and copy their movements in a process known as “scale-free correlation.” So, when one bird moves, its nearest neighbours respond in the same fashion and this propagates aware=like movement pulsing throughout the entire flock. However, while I agree with this notion, I have my own personal hypothesis about how each bird detects the movements of its neighbor. It is widely known among ornithologists that all birds, including starlings, have many sensory receptors embedded in their skins, which can detect air pressure. I think that the birds use these receptors to feel pressure waves emanating from the flapping wings of their neighbours and instinctively respond by flying in the same direction but keeping enough distance to avoid collision. It is not easy for me to prove this, of course, but if I could, it would make the news all over the world.

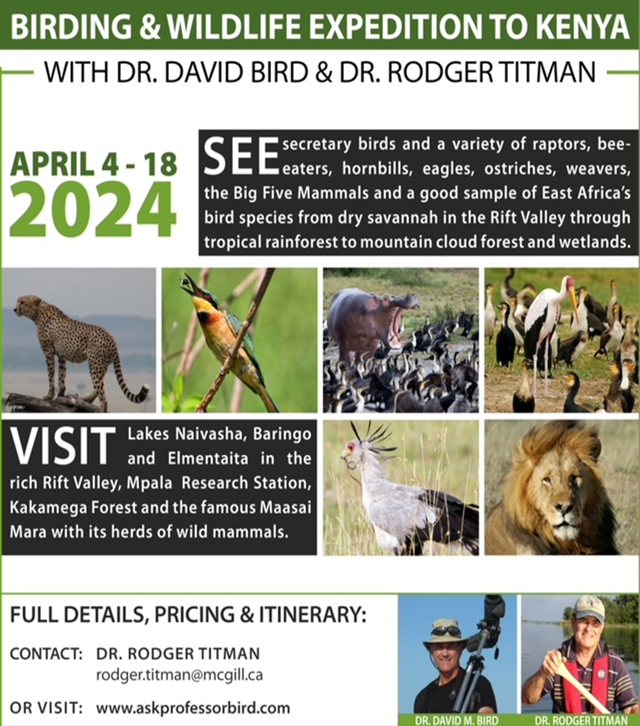

David M. Bird, Ph.D., Emeritus Professor of Wildlife Biology, McGill University www.askprofessorbird.com

David M. Bird is Emeritus Professor of Wildlife Biology and the former Director of the Avian Science and Conservation Centre at McGill University. As a past-president of the Society of Canadian Ornithologists, a former board member with Birds Canada, a Fellow of both the American Ornithological Society and the International Ornithological Union, he has received several awards for his conservation and public education efforts. Dr. Bird is a regular columnist on birds for Bird Watcher’s Digest and Canadian Wildlife magazines and is the author of several books and over 200 peer-reviewed scientific publications. He is the consultant editor for multiple editions of DK Canada’s Birds of Canada, Birds of Eastern Canada, Birds of Western Canada, and Pocket Birds of Canada. To know more about him, visit www.askprofessorbird.com or email david.bird@mcgill.ca.